0. CONTENTS

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The MBM Project - an overview

- External architecture of the MBM Database

- Internal architecture of the MBM Database

- Practical lessons of the MBM Project

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- Technical Appendices

1. ABSTRACT

We begin with a brief overview of the main themes and strategies of earlier documentation projects focused on Buddhist sites. The paper then turns to current needs of historians, anthropologists, and archeologists to make sense of their site-specific data by connecting them with wider regions and the work of other research teams. Georeferenced mapping is now both technologically feasible and a relatively low-cost means to accomplish both goals. The main part of this paper comprises a tour through our cooperative, small-scale, unfunded and inexpensive research project, "Mapping Buddhist Monasteries 200-1200 CE Project" (http://monastic-asia.wikidot.com), that was embarked on in late January 2009. Our experience from the previous 43 months of work on the Project suggests that systematic, long-term, low-intensity work by a 3-person volunteer research team is not only feasible, but also capable of delivering speedy, good, accurate and generally useful results. However, a team of this kind would not be able to produce such results without taking advantage of either free of charge (or, alternatively, low cost) publicly available digital tools such as text-editors, Wikidot.com wikis, the Falling Rain Genomics map generator, Google Maps, Google Earth and of course the Internet more generally. The paper concludes with a discussion of other possibilities for both expanding the Project and creating a network of complementary databases to further our understanding of the Buddhist world. It also contemplates the sharing of our innovative mix of research strategies and technological solutions (as well as resultant data) with like-minded researchers and teams.2. INTRODUCTION

In the last century scholars from three fields have closely studied Buddhism: archeologists, Buddhologists, and comparative religionists. Generally speaking, each group failed for their own reasons to connect historical Buddhists in large-scale networks. Please forgive our simplification and caricature of these three fields: the reasons will emerge shortly. Archaeologists have excavated and studied individual sites or groups of sites, generally those no longer in active use as places of worship or pilgrimage. Such sites are located, for example, in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China. Funding sources, particularly national governments, typically have financed excavations only within their boundaries. The unspoken aim of such research has been to understand the past of the nation (e.g. the Buddhist heritage of India). Transnational stylistic similarities in sites have invoked and emphasized notions of primacy and influence (e.g. India's influence on Southeast Asia), rather than notions of network, connection, or interchange. The two foundational texts in this tradition are G. Coedes, The Indianized States of Southeast Asia (1964, English translation 1968) and A.L. Basham, The Wonder that Was India (1963). In contrast, however, Japan has had a decades-old tradition of research interest in Buddhism extending far beyond its islands-bound borders. Additional problems hamper the piecing together of archeological evidence beyond national boundaries. Publications have, of course, been in a variety of colonial languages (English, Dutch, French) and current-day national languages (Japanese, Chinese, Sinhalese, Tibetan, for example). Equally daunting for historians are the publication traditions within the field. Many excavations receive only a field report, often published years later in a journal of small circulation. Perhaps the archetypical examples of the difficulties that this system poses are the publications of the Archeological Survey of India. Results may have been published in a Report of a Circle (a region) or the annual national Report, both now available in relatively few locations. Indexing has been minimal. Buddhologists have traditionally studied texts. Their central concern has been to understand the core concepts of Buddhism and the "purity" of texts, flagging later accretions. A secondary concern is to analyze commentary in order to identify various "schools". The translation of and commentary on texts remains an active academic field. See, for example, Rules for Nuns According to the Dharmaguptakavinaya, by Ann Heirmann (2002) and the many translations of Tibetan Buddhist texts published under the auspices of the Dalai Lama. The commentary accompanying translations occasionally notice broad-scale connections between monasteries, but this feature has not been a central concern. The work of Buddhologists is, nevertheless, essential for an understanding of networks and connections across the larger historic Buddhist world. The texts themselves show wider influences of teachers, monastic traditions, and the interchange of teachers and students. Texts typically include arguments against "incorrect" views, which demonstrate familiarity with those very teachings, though the latter often originated far away. Records of doctrinal debates often record the origin of the debaters and sometimes that of those present. Hagiographies and biographies are often our best records of the movement of monks in search of a teacher, texts, or a particular practice. Comparative religionists have sought the core beliefs, such as ethics or metaphysics, in Buddhism, often with implicit or explicit comparisons to Christianity. The foundational texts in this tradition are the translations of Max Mueller's Sacred Books of the East (original volumes published in 1879, series continued for almost a century). Their focus has been on belief and texts, rarely on doctrinal debates, differences and conflicts between monasteries, or long-distance connections of teaching and interchange of scholars. Though there has been some self-doubt about the field (see, for example, How to do Comparative Religion edited by Renˇ Goth—ni, 2006) the field still generates thematic comparisons across various religious practices (see, for example, Splitting the Difference: Gender and Myth in Ancient Greece and India by Wendy Donniger (1999). In the last two decades a few scholars of history and the history of religions, archeologists, and even practitioners have become interested in large-scale historical institutional and intellectual connections. To illustrate this trend we call attention to a few such scholars: Jonathan M. Kenoyer for encouraging study of the Indus Valley as a civilization found across a broad area of western India and Pakistan (Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, 1998), Sheldon Pollock for his ideas of a Sanskrit oekumene, which included Chinese monks who came to India to study the language (The Language of Gods in the World of Men, 2006), Xinru Liu and Lynda Shaffer for their work on the movement of ideas and material culture between China and India (Connections Across Eurasia: Transportation, Communication, and Cultural Exchange on the Silk Roads, 2007), and Tansen Sen's work on the connections between trade and monastic exchange (Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: the realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600-1400, 2003). Our joint project has brought together a handful of scholars in the now technologically feasible task of locating monasteries and their connections. We seek to draw in additional scholarly archaeological and textual expertise to map and document the vast world of Buddhist contacts, influences and interchanges.3. THE MBM PROJECT - AN OVERVIEW

Dr. Stewart Gordon (Historian, USA) conceived the Mapping of Buddhist Monasteries Project ("MBM") and in January 2009 contacted anthropologist and IT specialist, Dr. T. Matthew Ciolek (Australia). He felt that a small group of researchers could jointly develop a substantial electronic database on Buddhist monasteries across Asia in the period of China's Tang dynasty (c. 600 - 900 CE). He also suggested that analysis of the data could further understanding of interactions between various monastic institutions. Ciolek immediately realized that we could divide the work into specific tasks and assemble the database in stages. Fortunately, he had the Internet, digital mapping and database expertise to judge the project feasible and give it a format. It was also clear that MBM would require the expertise of country and regional Buddhist scholars. Ciolek drew on his research interest in geography and the logistics of mediaeval transportation and communication networks of Eurasia and Africa for content and data. By August 2009, we had improved the layout and workings of the database and entered data on several hundred monasteries, culled from various research publications and the Internet. A second historian, Dr. Lizbeth H. Piel (USA), joined the team. Her expertise is in Japanese intellectual history, and she has taught courses on East Asia and World Civilizations. The three experts - contact details at http://monastic-asia.wikidot.com/nav:contact - have worked together harmoniously ever since. Needless to say, they welcome area specialists and Buddhologists, both established and emerging, to contribute to the project and provide corrections and addenda. Looking back at what is now more than three years of voluntary scholarly labor, the project seems to have multiple "faces", rather like the ancient four-faced Slavic god Svetovid. Traditional sculptures show Svetovid as a tall, bearded man on whose shoulders rested four different heads, each facing a different direction. In similar fashion, the MBM project seems to have four aspects: 1) Gathering and interpreting data remains a central activity. 2) Generating hypotheses about the broader Buddhist world based on the developing data set. This remains an exciting activity with hypotheses affirmed or rejected as we enter new data. 3) Learning how to collaborate with various scholars from different fields and with diverse regional expertise, and insuring that the database is useful to a wide spectrum of research endeavors. 4) Attempting to develop a set of general-purpose digital tools and procedures, which can be applied to other historical data-collection, data-documentation and data-mapping ventures. Let us now turn to the detail of each of these four aspects of the Mapping Buddhist Monasteries Project.Development of a factual knowledge-base

The MBM Project is an attempt to collate traceable and verifiable research data that deal with the location, characteristics and activities of Buddhist monasteries present on the Asian continent during the period 200 to 1200 CE. This work involves several steps. First we learn (from a variety of already known sources) or intuit the physical (printed materials) and online (data files, web sites) whereabouts of sufficiently detailed and documented data. Secondly, we find, clean and vet the factual information. Thirdly, we give the data a standardized logical structure and typographical appearance. Fourthly, we reference and cross-link this information with other relevant data and/or documents in our digital database and generate associated digital maps. The result is that all of our collected information about monasteries is freely and easily accessible to ourselves and, at the same time, to any and all interested parties who have access to the Internet.Hypotheses about past historical developments

The second aspect of the project is that of a vehicle for generating and testing hypotheses about the overall forms; actual manifestations; geographical extent; temporal duration; social, intellectual and political overtones; and long-term consequences, of links and interactions found amongst the studied monasteries. Allow us now to explain our usage of some terminology. "Communications" refers to instances of movement of information between monastic establishments, i.e. to the unilateral dispatches as well as bilateral and multilateral exchanges of information, both in oral and written formats. "Contacts" suggest flows of abbots, monks, and students, as well as recommended lay personnel such as book-traders, copyists, painters, sculptors or architects. The term "Affinities" refers to on-going ties between monasteries: the establishment of new religious doctrines; transformations of intellectual or metaphysical frameworks; the development of artistic echoes and stylistic parallels found in the placement, layout, shape, materials, contents and symbolism of buildings, structures, murals and sculptures. "Alliances" refers to interactions that may be of a more practical nature: assistance with loans, funds possessed by one monastery and made available to another, say, for urgent repairs and building projects, sutra-copying projects, the acquisition of manuscripts and pieces of artwork, or enlargement of land holdings. Of particular interest are inter-monastic coalitions and joint political activities aimed at security in unsettled times or periods of government oppression. Whether data exists to answer these questions remains at present unknown. It is clear the database requires a much larger volume of data on inter-monastic interchanges than we currently possess to move beyond mere speculative extrapolation from scattered anecdotes.An Experiment in Collaborative Methodology

Two dynamics are at work in the MBM project. The first is to find an efficient mix of research and data-storage/data-publication procedures. This push for efficiency is, of necessity, tempered by the actual skills of the collaborators, and especially the need not to ask for too much rapid-scale learning in order to contribute to the database. Preliminary results of our investigations show that our team's initial preference for the use of strategies such as MOSAIC, BAZAAR, DISTRIBUTED, OPEN-ENDED, COTTON, and RONINS (see Appendix 1 for an explanation of these concepts) proved, on the whole, to be a reasonably advantageous one, albeit not to the extent that we originally hoped. Appendix 2 considers key characteristics and drawbacks of some electronic tools, which are commonly used in the humanities and social studies. Several of them are worth serious consideration, for they are free of charge, generic, off-the shelf software applications and/or online digital work and mapping environments. Our general experience with these tools suggests, for example, that research projects that are conducted chiefly in languages based on the non-Latin script will not fare well with standard text editing software. Likewise, projects that intend to make heavy use of dynamically scaled digital maps will not benefit from exposure to the Falling Rain Genomics' mapping technology. Appendix 3 considers the human side of collaboration: the allocation of tasks and responsibilities within a research team. We continue to search for work arrangements that seem to be good at harnessing the skills and enthusiasm of a team of multi-skilled and multi-temperamental unpaid volunteers. After some three and half years of joint activities, conducted individually and/or in parallel with other team members, the bulk of our responsibilities in this Project tend to be carried out individually. The overlap of responsibilities among team members remains relatively low.Development of a simple, general-purpose digital research tool

The fourth aspect of our work is the testing of various data gathering, data-storage and data-presentation tools and procedures. We search for a simple and reliable technical solution that can serve the generic needs of many other projects as well. We hope that other researchers in the field of humanities and social sciences, and especially in the field of archaeology, history and anthropology of Buddhism, will be tempted to use the MBM-tested digital tools to better organise their ever-growing knowledge of things other than monasteries. Indeed, our long-term goal in establishing the collaborative Mapping Buddhist Monasteries project is actually to launch the database that hopefully will become a node in the greater archipelago of compatible and interlinked research projects. Such a network of databases with georeferenced and cross-referenced information about roads, trade-routes, palaces, battlefields, gardens, water-tanks, sacred places, astronomical observatories, bridges, fords, mountain passes, mints, fortresses, watchtowers, light houses, beacons, petroglyphs, murals, sculptures, hoards of coins, caravanserais, places of worship, hermitages, ashrams, places of learning, houses of healing, harbours, shipyards, mines of ores, smelters, markets for slaves, sources of precious stones, and so forth - would certainly become a wonder to behold, a true Golconda of solid, correctable, mappable and reusable data nuggets. Therefore, the remainder of this paper will be dedicated to showing how individual nodes within such a future archipelago of interconnected databases could be conceptualised and constructed. To this end we will outline the logic and workings of our Online Database of Georeferenced Buddhist Monasteries. We shall list its major component parts, their overall external configuration and internal informational arrangements, as well as their key interdependencies, linkages and associated technical procedures. The final section will offer some practical conclusions. We trust that this paper will be useful to all those scholars who consider building their own collaborative online databases. We also trust that it will be of value and interest to those scholars who may be tempted to join the MBM research activities.4. THE EXTERNAL ARCHITECTURE OF THE MBM DATABASE

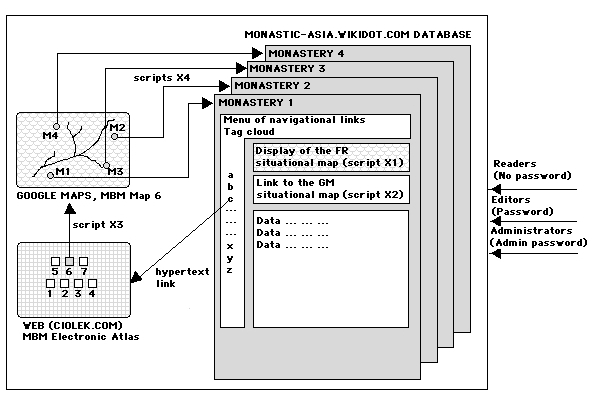

The MBM Database is a public access information system. It involves an interaction between two groups of digital tools (i.e. devices, software applications, work environments/platforms and data files). First, there are tools that exist on personal computers of the members of the Project. Secondly, there are tools that reside on the Internet. Interaction between these two groups of tools is initiated and accomplished by the logic of their connections (hypertext links and scripts) and procedures (tasks, actions, activities, operations). The overall configuration of such devices, connections and procedures is shown in Figure 1 below.and maintenance of the MBM Database & MBM digital maps.

4.1. MBM-related tools and procedures on team PERSONAL COMPUTERS

Software toolsT application - plain text editing software, such as Tex Edit Plus (for Mac OS X) or E Text Editor (for Windows); E application - Google Earth mapping software; B application - a Web browser (Firefox, Internet Explorer, etc.). K data files

These are data files in X4 script (see Appendix 6), i.e. with a code written in KML (Keyhole Markup) language (Wikipedia 2012k). The files are used to define functions and format appearance of sets of mappable geographical data. The number of such files depends on the number of maps listed in the CW visual catalogue module (see Section 4.2 below), which - ideally - should correspond to the number of maps published with the help of the GM module. Thus in the August 2012 version of the MBM Project there were seven KML files, one for each of the seven maps of Asia's regions. These maps range from MAP A. MONASTERIES NORTH-WEST through MAP D. MONASTERIES CENTRAL-CENTER to, finally, MAP G. MONASTERIES SOUTH-EAST. Therefore, the relevant KML filenames range from "input-geo-monasteries-north-W.kml" to "input-geo-monasteries-central-C.kml" and "input-geo-monasteries-south-E.kml", accordingly.

The K files contain information about (a) individual names and symbolic representations of the monasteries, (b) monasteries' placement (i.e. lat/long coordinates) within the mapped terrain, as well as (c) details of the unique Internet address of detailed records for each of the mapped monasteries stored in the MBM database. All of this information is succinctly expressed through the code compliant with Keyhole Markup Language (KML). The KML file is subsequently uploaded into the GM module i.e. the Google Maps online mapping environment. A fully functional, ready-to-be-used version of the X4 script is listed in Appendix 6. Production of the K data files

This step involves composition and editing operations (using the T application, i.e. the text-editor) applied to plain text documents with georeferenced information expressed in KML code. The resultant file is given a meaningful name, and a mandatory ".kml" extension, for example, "input-geo-monasteries-south-E.kml". These updates take the following form: (a) new or corrected information is copied to a temporary text file; (b) the data are sorted such that monasteries from a particular geographical region (defined by latitude and longitude values of their bounding boxes) are grouped together; (c) a master text KML data file for a particular region is opened (say, "input-geo-monasteries-south-E.kml"); (d) for each new monastery a fresh entry is created and filled with new information; (e) updates and corrections to old entries are inserted into the KML file, when necessary; and (f) the master-data file is then saved and closed. All this work is done on a researcher's personal computer with the help of a simple standalone text-editing program. Full function word-processors (see Appendix 2) are avoided. This is to ensure that extraneous formatting does not inadvertently contaminate the KML documents. Verification of the K data files

This is a syntax check performed on records comprising the K file. The check is done via the E application, i.e. Google Earth (http://earth.google.com). If testing reveals a problem, the offending file must be re-opened using the T application. All modified/added lines of KML code plus data need to be carefully inspected for the possible presence of small but fatal typographic errors. This process is repeated iteratively until the KML data file performs without error. Only then we are ready to alphabetically sort the newly added data entries in the master KML data file. With this step successfully completed (and tested once more) we are ready to connect, via the administrator's password, to our private workspace of the online mapping environment of Google Maps (i.e. connect to the Internet-based GM module).

4.2. MBM-related tools on THE INTERNET

The MBM DatabaseThis is a wiki-style work environment located on the "monastic-asia" sub area of the Wikidot.com server (Wikidot.com 2012b). This data-storage module performs two interlocking functions. It is a descriptive text-based catalogue (i.e. a database) of the studied monasteries as well as the MBM's primary reference point to be used in citations and acknowledgements. The use and navigation across this database is supported by a set of technical pages, that is, MBM wiki pages that hold the Project's scholarly apparatus and navigation shortcuts. All Internet users can readily view (and in most instances readily copy) all component parts of the MBM Database. However, only registered members of the MBM team can edit (create, modify, rename, delete) the structure and/or contents of the Database. The MBM Database grew in a handful of bold leaps as well as in a series of shy, hesitant steps. At the time of its inception (late Jan 2009) it consisted of a single reference to a single monastery, namely, the "Ravak monastery, (near) Hotan, Xinjiang, CN". This entry was followed the same day by two more addenda (entries #2 and #3). One for the "Abhayagiri monastery, (near) Anuradhapura, North Central Province, SL" and the other one for the "Mihintale monastery, (near) Anuradhapura, North Central Province, SL". Very soon many other data entries were added to our collection. The MBM Database started handling information about an ever-increasing range of georeferenced places: 176 monastic institutions (Aug 2009), 476 institutions (Sep 2010), 530 (Oct 2011), 551 (Apr 2012) and 574 (Aug 2012). These retrospective figures suggest that our data collection has grown at an average speed of approximately 160 additional monasteries a year, or about 14 entries a month, that is, one addendum every second or third day. The MBM Database is discussed in detail in Section 5, The Internal Architecture of the MBM Database, below. The CW visual catalogue module

This is a web-based publishing environment that contains the MBM electronic atlas area (as defined by the X3 script). This area has been established at http://www.ciolek.com/GEO-MONASTIC/geo-monasteries-home.html. This is a web page, which holds a visual catalogue of MBM maps published via the GM module. In Aug 2012 the CW module provided direct and interactive access to seven contiguous Google Maps' maps, which covered regions of the Asian continent relevant to Project's activities. The maps in question are: MAP A. MONASTERIES NORTH-WEST (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between Lat 39.0 - 60.0 N and Long 55.0 - 99.9 E),

MAP B. MONASTERIES NORTH-EAST (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between Lat 39.0 - 60.0 N and Long 100.0 - 150.0 E, incl. today's Korea & Japan),

MAP C. MONASTERIES CENTRAL-WEST (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between Lat 26.0 - 38.99 N and Long 55.0 - 71.9 E),

MAP D. MONASTERIES CENTRAL-CENTER (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between Lat 26.0 - 38.99 N and Long 72.0 - 99.9 E),

MAP E. MONASTERIES CENTRAL-EAST (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between Lat 26.0 - 38.99 N and Long 100.0 - 150.0 E),

MAP F. MONASTERIES SOUTH-WEST (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between 10.0 S - 25.99 N and Long 55.0 - 99.9 E) and

MAP G. MONASTERIES SOUTH-EAST (a map with details of up to 200 monasteries mapped in the zone stretching between 10.0 S - 25.99 N and Long 100.0 - 150.0 E). The GM mapping module

This is an online mapping environment located on the Google Maps (http://maps.google.com) server. This environment has two aspects. One of them is public, and the other private (i.e. password protected). The public side of the GM module can be easily accessed by means of an X2 script. The password-protected GM area requires users to have a Google account (e.g. by registering with Gmail.com). They must then define the number, names and the spatial extent of the required maps. Finally, the researcher, using a variation on the X4 script, uploads details of the studied mappable information. The X4 script enables a reader of any of the seven regional maps to select on the map a monastery of interest and jump (via a hypertext link) directly to the appropriate wiki page (published as a part of the MBM Database) with the full list of factual intelligence about that monastic institution.

Google Maps is a free-of-charge, general-purpose online mapping facility. For practical reasons this environment has an internal technical limit on the number of mappable elements that can be displayed within a single map.

The managers of the Google Maps public mapping tool have set this limit at 200 (i.e. two hundred Points (each with one pair of lat/long coordinates), or two hundreds segments (each with two pairs of lat/long coordinates) that can form straight or meandering, continuous or broken Lines and/or edges of Polygons). In practice it means that for a collection of say 250 mappable elements, one needs to define and build two online Google Maps (each containing less than 200 objects). This is why the MBM Project started with one online map, and as the accumulated data grew, the number of related maps in the CW and the GM modules grew in step. The FR mapping module

This is an online mapping environment located on the Falling Rain Genomics' Global Gazetteer server (http://www.fallingrain.com/world/index.html). This is a free-of charge service. It can be used by anyone who follows details of the X1 script (see Appendix 4). DW online documents

They are a vast range of electronic documents, and other clusters of online information on art, culture, history and architecture of Buddhism. These materials are available from the variety of web servers and online databases from many hundreds of places all over the world. OW online documents

These are various sets of partially connected, partially isolated web sites and web-based information services residing at a plethora of online addresses. These web-based materials deal with a number of topics, and the most of them are not concerned with Buddhism or Buddhist studies.

4.3. MBM-related linkages across THE INTERNET

These online connections are made through a series of computer scripts and hypertext links. The X1 script (see Appendix 4)This script connects each of the MBM monastic records of the MBM Database (on the wikidot.com server) to the low-scale general situational maps, with a separate map for each of the separate monasteries in the MBM Database. These maps are generated on the fly by the FR module (residing on the Falling Rain Genomics server). The X2 script (see Appendix 4)

This is a script that connects each of the MBM monastic records of the MBM Database (on the wikidot.com server) to the GM module (on the Google Maps server). A separate variable-scale (from very low to very large scale) map for each of the separate monasteries in the MBM Database is generated on the fly by the Google Maps service. An ordinary MBM-CW hypertext link

This link connects the whole of the MBM Database (on the wikidot.com server) to the MBM's electronic atlas enumerated and annotated in the CW visual catalogue module (on the www.ciolek.com web server). The X3 script (see Appendix 5)

This script joins MBM's electronic atlas listed in the CW module to the regional maps published within the GM module. A separate variable-scale map (ranging from a very low to the very large scale) for each of the distinguished regions is generated on the fly by the Google Maps service. Each of these regional maps is fully interactive and equipped with an X4 script (see the next paragraph). The X4 script (see Appendix 6)

This is a script, which, among other tasks, also forms hypertext links to join individual map symbols (as displayed on regional maps from the GM module) with the appropriate entries of the Wikidot.com-based MBM Database. A set of ordinary MBM-DW hypertext links

These links connect individual data nuggets from the MBM Database, as well as entries from the database's bibliography page to the DW modules, i.e. the sources of Internet-based information. Several OW-MBM/GM ordinary hypertext links

These numerous links connect individual web pages of the Web at large with various portions of the MBM database and of the GM module. In June 2012 there were 697,089,482 web servers in existence, which have supported activities of some 30 million individually named web hosts (Netcraft 2012). Each of those hosts can sport anything between one and several thousands of individually addressable web-, databases- and wiki-pages. The manifold web pages have been constructed across many hundreds and ten of thousands of places in world and are linked with each other via countless numbers of explicit hypertext (html and & wiki-style) links. They are also linked with each other in a virtual manner, due to the web content-discovery and Internet address-discovery of search engines such as Google (http://www.google.com), Yahoo! (http://search.yahoo.com) or Bing (http://www.bing.com).

4.4. Main MBM-related procedures on THE INTERNET

Georeferencing the dataThis process involves investigations aimed at linking (Hill 2006, Wiki.GIS.com - The GIS Encyclopedia 2012b) the monastery in question to its exact spot in physical space. Georeferencing of historical data is a complex, painstaking and fact-hungry operation. It requires intensive parsing of information contained in relevant books and web sites. It is a search for all extant scraps of information, however minute, that may cast additional light on the appearance and physical whereabouts of the investigated establishment. All gathered intelligence is closely examined, compared and interrogated in the manner worthy of Hercule Poirot or George Smiley. Competing inferences are juxtaposed and weighted; settled conclusions are ready to be reconsidered in the light of fresh additional information. Our team's experience teaches that this exercise involves seven consecutive steps: (i) Naming the place - development of a detailed list of all current and historic names (including all multilingual spelling permutations) of the monastery to be georeferenced. (ii) Describing the physical attributes of the place - development of knowledge of the monastery's prominent physical characteristics (e.g. tall structure vs. squat; compact vs. sprawling one; walled vs. unbounded; one with steep vs. flat roofs; stone structure vs. brick structure, walls of some colour vs. walls of some other colour, a monastery with a prominent gate vs. one with no such a gate, zigzagging path to the place vs. ordinary/unremarkable path, and so forth). (iii) Situating the place in the environment - development of knowledge of the monastery's immediate geographical context (e.g. 3 miles north-east of landmark L, next to crossroads, a day of walking on the way down from a mountain pass M, by a riverbank, overlooking a lake, on the hill's crest, on an N/S/E/W slope of the valley, on the outskirts of settlement S, etc.). (iv) Locating the place on a map or aerial photograph - initially a general, then progressively more specific determination of the physical whereabouts of a monastery that goes by one of the standard and variant names that known to us, say P, Q, R, etc., and is also known to be situated in some characteristic manner relative to the terrain features X, Y, Z, etc. This stage matches named monasteries' known ecological context (see step iii above) with observed ecological characteristics of the mapped/photographed environment. (v) Identification of the place - weighing the probabilities that the known structure (or its prominent part, such as the great hall, pagoda, stupa, the main gate etc.) with known physical characteristics (see step ii above) does in fact correspond to an object/feature that (a) has similar apparent physical attributes (as depicted in the aerial/satellite photographs), and - simultaneously - (b) is situated in a physical place confirmed through step (iii) above. In order to perform this task well a researcher needs to train himself in the art of forensic examination of aerial photographs and making informed interpretations of presence/absence of vegetation, undulations of terrain, distribution of solid shapes and faint shadows, as well as subtle traces and intimations of recent and/or long-discontinued traffic of people, animals and vehicles (Wilson 2000). (vi) Measuring its lat/long coordinates - getting as detailed as possible a reading of the lat/long coordinates of the structure depicted on maps and photographs. Latitude and longitude measurements can be calculated by hand from extant paper maps. Better still, they can be obtained electronically via the "LatLng Tooltip" provided by Google Maps Labs page of the Google Maps system. Obtained readings need to be taken as closely as possible to the centre of a structure determined in step (v) above and expressed decimal degrees, a measurement system where latitudes South of the equator and longitudes West of the zero meridian have negative values. The more detailed the measurement, the better. A measurement with 3 decimal points has an approximate precision of plus/minus 55 meters (at the equator). Four decimal points result in precision of plus/minus 5.5 meters (Wikipedia 2012l). (vii) Recording the georeferenced data - monastery's standard name and coordinates are encoded within an appropriate KML-formatted data file (i.e. in one of our K files). This file is subsequently verified and made into the X4 script. By the end of this seven-step operation, however, there remains the inevitable question of the data's accuracy - as opposed to the mere precision of one's measurements. Obviously, precision and accuracy are not synonymous with each other (Wiki.GIS.com - The GIS Encyclopedia 2012a). No matter how carefully we work, there is always a chance that some unnoticed clerical or analytical error might have crept into our georeferencing endeavours. All our georeferencing activity is, therefore, always an ongoing hypothesis making activity. For this reason, each of our MBM conclusions concerning the exact location of the named monastic complexes takes insurance. This is a number that indicates whether the actual placement of a monastery in the physical terrain is likely - in the light of the available information - to fall within 200 m, 2 km or 20 km of the point indicated by our coordinates (see "Coordinates' accuracy indicator" in Section 5.5 below). In August 2012 the MBM project has georeferenced 574 monasteries. The overall discrepancy between the MBM and the real-life lat/long coordinates was judged to be: no greater than 200 meters - 37% of cases, no greater than 2,000 meters - 42%, no greater than 20,000 meters - 22%. Maintenance work on scripts and hypertext links

Changes to information in the X1 and X2 computer scripts (see Appendix 4) are simple and swift. They can be very easily accomplished by invoking an edit mode for a particular wiki page in the MBM Database. The X3 script (see Appendix 5) situated within the CW catalogue module requires only rare amendments. This script gets updated only at the times when there is a change to the overall number of maps displayed in the CW and GM modules, or when there is a modification to the overall color-coding scheme of various religious traditions. All the edits are performed on a text file "geo-monasteries-home.html" situated on the Dr Ciolek's personal computer. This file is subsequently uploaded to the MBM electronic atlas page on the www.ciolek.com server. Finally, there are frequent periodic additions to and amendments of data details in the KML files containing the X4 script (see Appendix 6). Development and maintenance work on the MBM Database

MBM Database edits are also frequent. These editorial interventions are a series of modifications, additions and deletions applied to the database content, structure and appearance (in other words, to the essential trinity of information in digital formats). The electronic tool used for such editing is the B application, a web browser that connects to the MBM's Database area stored on the Wikidot.com work platform. According to information offered by the MBM Database's logbooks, toward the end of August 2009, that is during the first 8 months of the wiki site's existence there were 176 data pages, that is pages with details of monastic institutions that were known to us at that time. In addition there were 79 technical pages created as tools for internal navigation, and scholarly support for our research. The overall number and fine-grain details of both content and technical pages continue to evolve. As mentioned, during the first 8 months of our operations the content side of the MBM Database grew at a speed of approximately one new and unique addendum (new data page for a new monastery) about every two or three days. At the same the number of the technical pages grew initially at the very rapid pace of 10 new pages a month, only to stop almost entirely once it reached the level of approximately 80-90 technical pages. Both the content and technical pages were subject to numerous changes and adjustments. By the end of the first eight months of our operations the MBM Database comprised 176 data pages and 79 technical pages. The data pages have been modified a total of 2,925 times. This figure suggests an average, of 16.6 modifications per data page, or one modification every two weeks. The initial group of 79 technical pages, however, has received a total of 299 modifications. This means that on average each of the technical pages received 3.8 revisions each, or about 1 modification every two months. All in all, when both content and technical pages are treated as single set, the internal logs of the MBM's wikidot.com site show that in some cases changes and modifications to the data and documentation were numerous indeed. All 255 pages of the MBM Database's site extant at the end of August 2009 have been revised least ten times. Moreover, 37 of those wiki documents (14.5% of entire sample) would undergo at least 20 revisions each. Periodic updates to MBM maps in the GM module

Every now and then, approximately at the time when there would be 10-12 "charted" yet still "unmapped" records, those records' details are noted in a temporary text file. Names and coordinates of new monasteries are copied from the database records so that the relevant K files (i.e. the KML data files) can be updated, checked against the E application and finally, uploaded into the MBM's workspace at the GM module. The semantic tag "charted" refers to the fact the a database entry has been linked (via X1 and X2 scripts) to the situational maps generated by the FR and GM modules on the Falling Rain Genomics and Google Maps servers respectively. At the same time, the tag "mapped" means that information about each of the hitherto "unmapped" monasteries has been incorporated in the respective K file and successfully placed on the appropriate map from the suite of regional maps generated with the help of the X4 script. Naturally, records whose geographical coordinates are unclear continue to be treated and tagged as "uncharted" and "unmapped". Once the KML data file is successfully tested on a personal computer against the E application it needs to be moved to an appropriate portion of the Google Maps work environment. In practice it means that an old online regional map is opened for editing, its meta-details are adjusted where necessary, and the existing KML code is replaced (i.e. overwritten) with the new one. This procedure is a straightforward operation and is amply guided by online prompts and instructions. Online promotion of the MBM Database

Promotion means the creation of annotated links on web pages controlled by members of the MBM team. For example, in January 2009 it meant placement of links and notes on the www.ciolek.com home page. In January 2011 it also meant placement of an abstract describing the Project to the Asian Studies Monitor web site, at "http://coombs.anu.edu.au/asia-www-monitor.html" address, and ditto, at The Best of The Asian Studies WWW Monitor Blog (on 18 January 2011), at "http://asia-www-monitor.blogspot.com.au/" address) as well as "seeding" the WWW at large with notes on the Project via judicious use of mailing lists such as THE ASIAN STUDIES WWW MONITOR e-journal (over 9,260 subscribers), published by the ANU (http://coombs.anu.edu.au/asia-www-monitor.html), or the trade-routes-mailing list (over 200 subscribers) (http://mm.isu.edu/mailman/listinfo/trade-routes). After a few years of these and other occasional promotions of the MBM Database, our team is pleased to note that, gradually, the Project started receiving a modicum of online visibility. In mid-June 2012, a Google search for the keyword string "Buddhist monasteries" has listed the MBM Database in 14th place (i.e. on the 2nd page of results) out of a total field of 1,440,000 relevant results. Also, the Google search for the string "monastic-asia.wikidot.com" located no fewer than 3,860 places on the Internet with a direct link to this address, and therefore with a degree of explicit interest in the MBM operations (Google 2012a).

5. THE INTERNAL ARCHITECTURE OF THE MBM DATABASE

The MBM Project publishes a distributed system of seamlessly joined information services. It is a worldwide cluster of hardware, software applications, data, and team members. The four separate servers that have been combined to develop the MBM information resources reside at four different geographic locations. These are: the Wikidot.com machinery and software (i.e. the MBM Database itself) - in Dallas, TX, United States; the www.ciolek.com server (i.e. the CW module) - in Canberra, Australia; the www.fallingrain.com (i.e. the FR module) - in Worcester, United Kingdom, and finally, the maps.google.com (i.e. the GM module) - in Mountain View, CA, United States. One of the conveniences of the MBM database is that anyone with an appropriate password can work with it collaboratively, regardless of time zone. These four information modules are accessible on a 24/7 basis from all Internet-enabled locations in the world. There are three level of access associated with those information modules: reader-level, editor-level, and service-administrator-level. The first level of access can be reached without any specific identification; the next two require separate passwords.

5.1. Access mechanisms

Access to the web-based CW visual catalogue moduleReaders and the MBM-editors can freely view all the data, with associated X3 script, and use their web browser's menu to view the document's html source code (a code, which includes details of the X3 script). They are also free to use the browser's in-page search command. Browsers can also be used to select and save to another document any portion of data and information published within the CW module. Changes to the structure or details of the CW module can be implemented only by the service's administrator, who is the owner of the admin-password, in this instance by Ciolek. Access to the Falling Rain Genomics-based FR digital mapping module

Readers and the MBM-editors can freely view all the data displayed within a miniature small-scale situational map. This map, a separate one for each monastery, is generated at the MBM monastic data pages by the X1 script. Readers and the MBM-editors can also use their web browser's menu to view the wikidots.com document's source code. The browser converts the code from a set of Wikidot.com markup tags to a set of their html equivalents. Therefore, readers and editors can also see details of the X1 script as well as use their browser's search-in-the-page command. Browsers can also be used to select and save to another document any portion of data and information published within the MBM Database. All MBM-editors can readily implement changes to the structure and/or details of the X1 script that glues Wikidot.com database pages to maps from the RW module. Access to the Google Maps-based GM digital mapping module

Readers and the MBM-editors can freely view and interact with all the data generated by the X4 script. Also, they can use their web browser's menu to view the document's source code converted from a set of KML markup tags to their Google Maps' java & html equivalents. This means that readers and editors can also see details of the X4 script itself, albeit the displayed source code borders on being unintelligible. Readers and editors can use their browser's in-page search command, as well as the GM module's search box within the GM world gazetteer. Only the owner of the GM module's admin-password can implement changes to the structure or details of the X4 script connecting each of the maps in the GM module to the appropriate monastic data page in the MBM Database. Access to the Wikidot.com-based MBM data-storage module (henceforth the MBM Database)

Readers and the MBM-editors can freely view all the data and all other information published on the wiki module. Furthermore, they can freely use the MBM's full-text-search box, as well as all navigation links and groups of pages marked with a given semantic tag. They can also use their browser's menu to invoke their browser's in-page search command. Browsers can also be used to select and save to another document any portion of data and information published within the MBM Database. In addition, the MBM-editors can use their individual, editor-level passwords, to enable them to use the widkidot.com suite of editing and file control tools and, thus, to create, modify, rename and/or delete any of the Database's page. However, only the MBM's administrator can modify the structure, behaviour and contents of the entire MBM Database.

5.2. Elements of the web-based CW module

This module (http://www.ciolek.com/GEO-MONASTIC/geo-monasteries-home.html) is home to the MBM's Electronic Atlas. It presents (a) a legend common to all MBM maps dealing with the Buddhist monasteries; (b) a set of small-size Interactive maps dealing with the regions of Asia covered by the MBM data-gathering activities, (c) hypertext links (all versions of the X3 script) taking a viewer to the GM module, which publishes a suite of larger, annotated and interactive GM maps with MBM monastic data.5.3. Elements of the map generated by the Falling Rain (FR) module

This data element (present on each of the MBM Database's monastic data pages) shows a miniature (3.5x3.5 cm) low-resolution satellite map of the relevant region of Asia. This is an inert, i.e. non-interactive map. It shows a given monastery's location, together with its name, within the larger context of state boundaries and undulations of terrain. This map is generated in real-time, on each instance of opening an MBM's data page that carries the X1 script (see Appendix 4).5.4. Elements of maps generated by the Google Maps (GM) module

The GM module carries the following six subsets of information, most of which are provided by the MBM editors:(a) a default hypertext link to "My Places" (i.e. Google Maps' individual work environment accessible via the owner's admin password).

(b) The map's name, the date of the most recent update and number of monasteries mapped on the map in question.

(c) The map's legend.

(d) A default interactive link, which can be invoked - if required - to download the map's KML file definition (i.e. the X4 script). Such a KML file, upon being opened, locally loads Google Earth application and displays the map with monastic information. Naturally, such a KML can be subsequently saved for further online and off-line interaction, or modifications.

(e) An alphabetic list of all monasteries depicted on the particular map. This list is an interactive one. If any monastery name is clicked-on, a small window with that monastery's summary information is displayed together with a pointer to the monastery's position on the map. If a hypertext link listed in such a window is clicked-on, that viewer is taken (via X4 script) straight to the appropriate monastery's data-page of the MBM Database. One can return to the GM environment by closing the freshly opened monastery's data-page.

(f) A variable-scale map of the region with the monasteries. There a "droplet" symbolizes each of the individual monasteries. Its colour encodes the monastery's main doctrinal affiliation. Clusters and groups of monasteries are represented by a set of concentric white circles. As in (e) above, when any monastery symbol is clicked-on, a small interactive window with that monastery's summary information appears on the computer screen.

5.5. Elements of the MBM Database - Data pages

The major and perhaps most visible part of the Project is its searchable and browsable collection of individual data sheets (see Appendix 7), each data page corresponding to an individual monastery. The information on the monasteries is standardised and collected according to a common, time-and-effort saving Template. The Template replicates across the MBM Database the unified appearance of the data pages and the pattern of data fields: The Monastery's NameThe monastery's name is stated together with its location within a geographical sub-area, administrative province and country. 2 letter country Internet codes indicate the last item, e.g. "IN" for India, "CN" for China, "TM" for Turkmenistan and so forth. The overall naming scheme is as follows: XXX (name), monastery/nunnery/hermitage, Proximity indicator (in/near/towards). The proximity indicators carry a technical meaning: thus "XXX monastery (in) YYY" = the monastery is situated, either exactly, or roughly within the boundaries of the YYY settlement. "XXX monastery (near) YYY" = the monastery is situated approximately no farther than 20 km from the YYY settlement. "XXX monastery (towards) YYY" = the monastery is situated farther than 20 km from the YYY settlement), YYY (the reference settlement), country's administrative province, the top-level political entity (= country), in which the monastery currently is situated. The country-coding scheme is a technical device that uses the current (current for the 2009-2012 period) political subdivisions of the world. Thus the famous Samye monastery (est. 766 and consecrated in 767 CE) is treated by the MBM Database to be presently situated in China, whereas between 766 CE till 1947 it was situated in the more or less sovereign country called Tibet. Similarly, Vrang monastery, (in) Vrang (est. in the 4th century CE) from the 1860s till 1917 was a monastery situated in Russian Empire, from 1917 till 1991 was a part of the Soviet Union, and from 1991 onwards - a part of a new independent country now called Tajikistan. Likewise, Somapura monastery (in) Paharpur (est. 7th century CE), in the years 1947-1971 was a part of East Pakistan, and since 1971, a part of the newly formed Bangladesh. In other words, the term "country" is an apolitical description, it does not reflect on the rights or wrongs of the Asia's political history. Raw Data and Notes

A holding area that permanently stores rough data (and references) for each of the studied monasteries. Coordinates' accuracy indicator

An indication of the likely precision of MBM-determined coordinates for a given monastery. For the sake of simplicity our data are marked with one of three possible values: the nearest 200 meters, the nearest 2,000 meters, and the nearest 20,000 meters. See also a note on "Georeferencing the data" in Section 4.4 above. The FR map

A miniature map depicting the topographical and political context of the monastery in question. It is generated at the FR module through the X1 script. See Appendix 4. A hypertext link (= X2 script)

A link to the appropriate area of the Google maps mapping environment. See Appendix 4. Data fields

A set of 17 data-fields that provide detailed descriptions of each of the researched monasteries. These fields are enumerated in Appendix 7. All data pages of the MBM Database observe the same typographical convention: a question mark "?" indicates uncertain information, fields marked with words "final data É" or "[missing data]" flag current lacunae and gaps in our factual knowledge, underlined words indicate the presence of a hypertext link. Semantic Tags

Each of the monastic data pages is annotated with Tags. The number of tags and their details vary from case to case. For example, a page for Ajanta monastery, (in) Ajanta, Maharashtra, IN is annotated as follows: "2km", " a", "cave", "India", "mapped", "murals", "South-Asia", "spot", "tradition?" These succinct tags mean that the discrepancy between the real-life location of the monastery and coordinates reported by the MBS is less than 2km, the monastery's name starts with the latter "A", the monastery is associated with the use of a cave or caves, is situated in India, has been mapped (i.e. its geographical coordinates have been determined) on a map published in the GM module, has murals (= wall/ceiling paintings), is situated in South Asia, it is a single monastic institution (as opposed to a place populated by a cluster of multiple, separate monastic establishments) and finally, the monastery's major Buddhist tradition is at present, undetermined). By contrast the Bamiyan monastery, (in) Bamian, Velayat-e Bamian, AF is annotated with the following tags: "200m", "Afghanistan", "b", "cave", "Central-Asia", "Huichao", "Lokottaravada", "Mahasanghika", "Mahayana", "mapped", "South-Asia", "spot", "Theravada", "Xuanzang". These tags additionally signal that the place was once associated with Buddhist worthies called Hui-chao and Xuanzang, respectively, and was used by monks subscribing (at various times) to the Theravada and Mahayana forms of Buddhism, as well as to the Lokottaravada and Mahasanghika sub-traditions.

5.6. Elements of the MBM Database - Apparatus pages

In addition to the data pages there are also these sections of the MBM site that directly support one's research activities. The scholarly apparatus pages include: Raw and temporary data pageA scrapbook, it is used for temporary online storage of raw, unprocessed and unverified information of possible future relevance to the MBM Project. Once this material has been used in other pages of the MBM Database site, the notes are deleted from this temporary page. Asia's chronologies page

Details of chronologies for the period (ca. 200 - ca. 1200 CE) for Arabian Peninsula, Burma, Byzantium, Cambodia, Central Asia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Persia, Afghanistan and the Transoxiana, Vietnam [Annam, Nam Viet, Dai Viet] and Vietnam [Champa]. Bibliography page

An alphabetic list of over 200 references to published materials. In Aug 2012 approximately half of such references were made to Internet-based publications (i.e. to the DW range of online documents. See Section 4.2 above). The MBM references to online materials observe the following convention: AUTHOR'S FAMILY NAME, Given Name, Publication Date, Publication's Title [with a hypertext link to a possible online publication, Place and Publisher Details, Details of the Hypertext Link, Version (date) of the online information in question - used only in references where the information is volatile, as is the case with live/frequently modified online material].

For instance: "ZEJMAL', T. and E. Rtveladze. 1999. Northern Tokharistan (pp. 131-133, 141-142 of Chapter 7, "Severnyj Tokharistan"), in: Brykina, G. (ed.). 1999. Central Asia in the Early Middle Ages. "Nauka" Publishing House. [www.kroraina.com/ca/index.html] (v. Aug 2009)". The Abstract page

Summary details of the MBM Project. Citation format page

Suggested citation formats for the whole of the MBM Database as well as for its individual sub-sections. List of Currently Unidentified Places

Not all monasteries known to have existed can be readily identified and located. A temporary list for these enigmatic materials contains available information about the * Institution's Name * Type of structure * Place in the literature * Name of the MBM researcher who first tried to locate the unidentified place in question.

For instance: "ZORMALA. Structure: stupa. Location: Surkhan Darya region, Uzbekistan. Mentioned in: Berzin (1994-2006). Investigated (so far fruitlessly) by: tmciolek, 25 Nov 2010." Map Scales & Measurements page

A file used to identify the approximate scale of the maps displayed in the GM module. These maps sport 13 sets of seamlessly connected scales that grow progressively from the very general level of 1:22 M (= 4.5 cm on the digital map equals 1,000 km) to the very detailed, 1:11 K, level (= 1.8 cm on the digital map equals 20 meters in the terrain). Sanskrit Fonts page

The Wikidot.com environment can readily store and display non-Latin fonts. Our Sanskrit Fonts page keeps a handy list of characters used in this language. These characters are ready for subsequent copying and pasting operations in other sections of the MBM Database site.

5.7. Elements of the MBM Database - Navigation pages

This is a set of MBM pages that aid readers, editors and administrators alike to orient themselves within the site and quickly progress from one portion of it to another. The hub of all the operations is formed by the site's Home page. There one finds the "Work in Progress Warning", the database's vital statistics - date of the last update, number of catalogued monasteries, as well a list of the 20 most recently created pages. Next comes, a page dealing with "Recent Changes" page. This is an ever-growing catalogue of all the MBM documents that have been created or modified since the site's inception. The catalogue is presented in reverse chronological order. Finally, there are Redirection pages as well, ones that help visitors locate desired information more quickly. In Aug 2012 the MBM Database contained only four redirection pages. All of them observe the same logic. For instance, a page http://monastic-asia.wikidot.com/basarh carries the following information: Basarh, Bihar, IN - Redirection - See Vaisali cluster, (in) Basarh, Bihar, IN.5.8. Elements of the MBM Database - Meta-information pages

Pages that carry additional information common to the whole of the Database. For instance:(a) Join-This-Site - a page with an invitation to interested volunteers to join or otherwise contribute to the Database, (b) Authors' Biographical Notes and Contact Details, (c) "Work in Progress" warning. One of the great features of the Internet is the ease with which people can visit a given information site, read it, and then copy and carry away published data and/or conclusions. Since the MBM Database keeps evolving and mutating, a prominently placed warning advises all visitors to exercise extreme care with the use the MBM provisional findings while the "Work in Progress" warning is on display.

5.9. Elements of the MBM Database - Site administration pages

These are the generic Wikidot.com pages with tools for modification of the wiki's appearance and online characteristics.5.10. Elements of the MBM Database - Menus of navigational links

Top Bar MenuCommon to all MBM Database pages, this horizontal panel links to:

(a) Four geographical subsets of database records

* CENTRAL ASIA: Central Asia - all pages, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Western China.

* EAST ASIA: East Asia - all pages, China, Japan, Korea.

* SOUTH ASIA: South Asia - all, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Kashmir, Ladakh, Lahaul Valley, Nepal, Pakistan, Sikkim, Spiti Valley, Sri Lanka, Swat Valley, Tibet, and Zanskar.

* SOUTH-EAST ASIA: SEAsia - all pages, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam.

(b) One topical (categories/aspects of monasteries) sub-set of the data-pages, plus

(c) Links to the Meta-Information pages (see above). Side Navigation Panel

Common to all MBM Database pages, a vertical panel with hypertext links to:

(a) The Home Page (note, the home page provides the "Work in Progress Warning" (see above), (b) Apparatus Pages, (c) a List of Monasteries A to Z, (d) Online Atlas A to Z (i.e. hypertext link to the CW module on "ciolek.com" website), (e) A list (in the inverse chronological order) of the Recent updates/additions, (f) Raw & temporary data page (see above), (g) Tag list, (h) Site Members details page, (i) Site Manager page, (j) "How to edit pages?" (a generic Wikidot.com help page), (k) "Search this wiki" query box (this is a generic Wikidot.com full-text search tool, see Section 5.14 below), (l) "Add a new page" command (a generic Wikidot.com subroutine).

5.11. Elements of the MBM Database - Other MBM Links

Navigation across the MBM Database is also carried out via hypertext links that are embedded in the passages of text. Internal links lead to other MBM pages (e.g. in the monastic data pages these are the links to "Other known nearby Buddhist monasteries"), while the external ones take a reader to the online world of the DW sites and documents.5.12. Elements of the MBM Database - Semantic tags

The Wikidot.com system gives editors of the MBM Database a powerful tool, in the form of "Tags". Tags are an editor-defined set of short (one word) annotations added to pages published on the MBM's site. Once established, these tags are automatically appear in three different locations: (i) As a local, page-specific Tag-list displayed at the bottom of each of the annotated pages,(ii) As a global Tag-cloud displayed in the Side Navigation Panel (see Section 5.10 above) and

(iii) As a global Tag-cloud displayed as a part the site Navigation pages. For an example of the two global tag-clouds in action see the page http://monastic-asia.wikidot.com/system:page-tags/tag/kashmir

Tag-clouds provide a swift visual representation of the relative frequencies of occurrence of terms used to annotate MBM Database pages. Tags are created to: (a) group data pages according to the first letter of their names - tags "a" ... "z"; (b) group data pages according to their geographical characteristics such as the names of regions, countries or sub-regions; (c) group data pages according to religious doctrines and sub-doctrines represented by the catalogued Buddhist monastic communities; (d) group data pages according to the presence of some of the more distinctive features of the catalogued monasteries. For instance, monasteries can form thematic groups such as "Clusters of monastic sites", "Cave sites", "Pagoda sites", "Stupa sites", "Chorten sites", "Murals sites", "University sites"; (e) flag associations with activities of the famous Buddhists: e.g. "Fahien", "Naropa", "Padmasambhava", "Sungyun", "Xuanzang", "Yijing" and so forth; (f) indicate the precision of our georeferencing endeavours, e.g. to the nearest "200m", "2km", "20km"; (g) indicate the day-to-day status our mapping endeavours. Thus monastic data pages can be annotated as being "uncharted", "unmapped" and, finally "mapped" monasteries; (h) take the reader to the technical sections of the MBM site - tags "redirect", "template" and "navigation".

5.13. Elements of the MBM Database - Editing Tools

These are a series of top-level commands for editing, structuring and managing the wiki's Pages, Links and Tags. These commands include: EDIT (invokes the edit mode for the wiki page in question), TAGS (adds/removes/modifies tags that annotate a given page), HISTORY (i.e. comparisons between all previous versions of a given page), FILES (views and manages any downloaded documents that are attached to the page in question. SITE TOOLS (lists all "broken links", i.e. links that await the creation of their respective local destinations, and "orphaned pages", i.e. all pages that are not linked to from any other local page) and OPTIONS PLUS (a group of powerful commands such as "Rename the Page" and "Delete the Page").5.14. Large-scale features of the MBM Database

Online Advertisement (can be disabled by the site's administrator)"At Wikidot.com we display 3rd party advertising on free sites to help us pay the bills and keep the most services free. Our algorithm tries to show ads in a non-disturbing way, e.g. logged-in users should not see any ads at all. We try to optimize ads so that they do not impair the user experience [...] To remove ads from your site, there are two simple choices: 1. Upgrade to one of our Pro plans -- even Pro Lite (for about $5 a month) removes ads from sites you are a master administrator of. [...] 2. If you are running an educational site (for your classes, student projects etc.) you could apply for the Educational upgrade. Also, ads are not displayed on any private sites." (Wikidot.com 2012c). See also details of Wikidot.com subscription plans (Wikidot.com 2012d). Search box

The Database is equipped with a standard Wikidot.com full-text search mechanism. This local search engine is operated via a search box (situated in the upper right-hand corner of the Top Bar Navigation Panel as well as at the bottom part of the Side Navigation Panel). This tool processes a search string (i.e. one or more words or numbers). The search is of the OR type, one which searches the MBM site for pages that match any of the specified criteria. In practice it means that a search on a string such as "Among the oldest Buddhist monastery cities with caravansarais and temples in Uzbekistan" retrieves not only the single target page that contains that comprehensive string (in this case, the search retrieves the page http://monastic-asia.wikidot.com/airtam) but, additionally, some 62 other pages as well. In other words, the Wikidot.com default search mechanism retrieves all pages that contain one or more of the following keywords: "Among", "the", "oldest", "Buddhist", "monastery", "cities", "with", "caravansarais", "and", "temples", "in", "Uzbekistan". The Wikidot.com search mechanism is not case-sensitive. Thus it readily retrieves information on "buddhist" and "Buddhist" antiquities alike. However, it always looks for complete words, not for fragments. Global corrections to the database pages' content or appearance

Unfortunately, the Wikidot.com software does not provide tools for a global (across the entire database) find-and-replace operation. This means that any systematic changes across the site need to be done manually, one-by-one. The MBM team regards the lack of such a database-editing tool as a very severe drawback of the Wikidot.com work facility. Backups

The Wikidot.com collaborative environment allows for manually activated backups of the published materials. However, one cannot restore from it automatically, and the backups do not include the history of page revisions. The backed-up material can be easily downloaded to a researcher's personal computer. Uploads

Any project residing on the wikidot.com servers can be enriched by uploads and attachments of additional files (e.g. numeric data, documents, photographs, etc.).

6. PRACTICAL LESSONS STEMMING FROM OUR WORK ON THE MBM PROJECT

Our experience from the previous three and half years (so-far) of work on the MBM Project suggests a handful of general conclusions: * Each research project is unique in the sense of its particular combination of intellectual and organisational legacy, ambitions and assets. Therefore, each project faces an idiosyncratic octarchy of logistical constraints (see Appendix 1). It is best to seek and select remedial strategies well before research work commences in earnest. * The skillful use of the research strategies can greatly reduce fundamental constraints and frictions characteristic of research activities. The following mix of work strategies: MOSAIC, BAZAAR, CENTRALISED, FROZEN, COTTON and GUARDSMEN seems to best attuned to the reduction of typical hindrances and delays. It does it work much better than the mix of strategies (i.e. MOSAIC, BAZAAR, DISTRIBUTED, OPEN-ENDED, COTTON, and RONINS) that we have adopted in 2009 for the purposes of the MBM operations (see again Appendix 1). * Research projects that are standardised around the use of Latin fonts only are the swiftest, easiest and simplest ones to implement. However, a research project can make light-to-moderate use of non-Latin fonts as well. First, in the FR environment, such a project will be able to use only simple plain text (ASCII format). Next, the Wikidot.com work environment is very comfortable with the use of Latin fonts with extensive diacritic markings as well as non-Latin (i.e. Asian) fonts. Thirdly, the Unicode encoding of text non-Latin fonts can be easily replicated (see Penn State University 2011) in all web-based documents (e.g. such as those published within the CW module) as well as in the KML-based data files and the resultant maps in the Google Maps display system. Ideally, however, such a research project should secure regular professional advice from a person with skills in the construction and display of documents with Non-English online information. * The experience of the MBM project shows that it is perfectly feasible for a team of several people, each of them operating from a separate geographical location, to implement a productive, long-term research project by means of Internet-based collaborative work environments and digital informational resources. * It is advantageous to have a team where more than one person performs each of(http://maps.google.com). the specialist tasks. It this manner the continuity expertise and operations is retained, even in the face of a given expert's departure. * The combination of the Wikidot.com work environment, a web site, and the FR and GM mapping environments works well. We recommend it to other projects. * The MBM Project publishes its data by means of four interlinked online publishing tools (i.e. the MBM database, the CW map catalogue, and the FR and GM map servers). It is a distributed information system. This arrangement works well for our purposes. However, this is not an inflexible requirement. The CW module could be easily taken out of this equation. The functionality of a more centralised project would not be diminished, as long as the script X3 with definitions underpinning the display of the MBM's visual catalogue of online maps is written in a code that is appropriate to Wikidot.com requirements. In other words, this catalogue of GM maps could be just as easily installed not on a separate CW web page, but on one of the navigation pages of the MBM database itself. * The greatest deficiency of the MBM database is its inability to carry out a global find-and-replace command for editing its constituent pages. Instead, repetitive corrections have to be performed on the individual page-by-page basis. Until the day comes when Wikidot.com developers create a command for implementing global corrections to all pages of one's wiki, the Wikidot.com platform will continue to resemble a falcon a missing talon. * The editors' and administrator's access to the Project's manifold work-environments is controlled by appropriate keywords. Ideally, such keywords should be linked to the generic function a person performs within a research team, and not to the specific individual. A copy of all such passwords needs to be kept in a secure physical location and be accessible to more than one of the team-leaders. This is to ensure that the work on the project is not hindered by the sudden departure or recalcitrance of the team member with knowledge of the password. Naturally, all these passwords should be secure, i.e. difficult to figure-out by an outsider. They also need to be changed, whenever such a change is warranted.Possible further uses of monasteries' data collected at the MBM Database

At present the MBM Project is focused on the use of information contained by the MBM Database for the study of inter-monastic communications, contacts, affinities and alliances. However, other analyses of our materials are already feasible.For instance, among the data pages that comprise our MBM database, there is field no. 16, "Additional notes" - a placeholder for details of the size of the monastic population in a given establishment. Sometimes this field stores information only on the overall size of the monastic population in a given place. Sometimes, all we have managed to achieve is to locate information only on the number of cells in a given establishment. In other instances, we have been more fortunate. Occasionally we have managed to collect data on both the overall number of monks and the number of their cells. With these snippets of incomplete but interrelated information in hand, we might be able to take a step forward. Average (or the most plausible) numbers can be easily calculated from the data on record, and extrapolations can be worked out. In other words, missing factual data on the numbers of buildings, monks, and caves/cells can be, in principle, populated with the most likely values, values that have been derived from simple statistical modelling.

Additional studies are also possible. This is because digital data published at the GM module in the form of the MBM maps are amenable to secondary analyses. Such analyses can generate ample descriptive statistics, as well as on some occasions - cross-tabulations. Thus, possible future investigations might include research on:

(a) The average distance between pairs of the most proximate monasteries.

This could be either the length of the distance as the crow flies, or the length of a path accessible to a travelling man, or to land transport. Such information can be easily gleaned from the MBM maps published in the GM module by using an online "Distance Measurement Tool". This tool is available from the Maps Labs section of Google Maps (Google 2012b). Data on distances between neighbouring monastic establishments can be easily juxtaposed with available information pertaining to the type and intensity of interactions between the monasteries. Will pairs of nearby monasteries be more likely to show cultural and doctrinal affinities, as well as political alliances? Will the more distant establishments be interested in the establishment of contacts, i.e. the regular exchanges of personnel? At present we do not know the answers to these questions.

The term road in this context means path or continuous track that is accessible to (i) wheeled transport and/or (ii) a train of pack animals. Such an analysis could help to clarify and quantify the strength of an association between physical placement of monasteries and the flow of trade and large-scale transportation routes. (c) The placement of monasteries relative to various types of proximate human settlements.

Western (i.e. Christian) monasticism has an old adage, a Jesuit proverb: "Bernardus valles, Benedictus montes amabat, oppida Franciscus, magnas Ignatius urbes." or, in a rough translation "The Cistercian order (founded by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, 1090-1153) loves valleys, the followers of St. Benedict of Nursia (480-543) - mountains, Franciscan monks (an order of funded by St. Francis of Assisi, 1181/1182-1226) seek towns, while the Jesuits (an order founded by St. Ignacio of Loyola, 1491-1556) prefer large cities." (Ciolek & Dobrowolski 1965:58). A question, therefore, arises - are there any geographical parallels with the West? Are there any spatial preferences that would be characteristic of the major monastic traditions of Buddhism? This is a question that, at some point in the future, can be answered with the MBM's spatial data. (d) Location of a monastery within the physical folds of a landscape.